In reading my classmate’s blogs on Graffiti, many common themes emerged. One of the more prominent themes was that of graffiti as vandalism vs. graffiti as art. I found that the entries by Lauren and Erika, when read together, complimented each other and provided a good basis for understanding graffiti’s role in the community and the changing ideas surrounding it, which help explain the reluctance of some to accept artistic graffiti as art.

Lauren’s overall argument seems to have been that artistic forms of graffiti (“graffiti art”) reinforce and represent images of a community. One aspect of her blog that provides a real contribution to the understanding of graffiti is that she clearly differentiates vandalism graffiti from art graffiti. Rather than taking the, ‘I know it when I see it,’ approach that many other students chose, she clearly differentiated graffiti that “result[s] from a desire to create artwork” as “graffiti art”, and destructive graffiti with ties to violence or crime as “vandalism graffiti.” She provides examples of each type from Vancouver’s Kerrisdale neighborhood and explains how the vandalism graffiti at a bus stop does not reflect the community’s image for itself, whereas the artistic murals represent pictorially the multicultural, diverse, higher socio-economic status of Kerrisdale as a community. Murals, because they represent the community, are allowed to stay, she says, whereas vandalism graffiti is quickly removed because it subverts the image of itself Kerrisdale wants to promote. Thus, she shows how art graffiti is a positive part of a community.

Marais and Taylor similarly discuss how graffiti comes in many forms and thus requires a non-homogeneous solution (2010:57). They also contrast publicly sanctioned graffiti art with vandalism graffiti, which they usually define as tagging. Like Lauren, Marais and Taylor believe that graffiti has a place in the community and they add that artistic graffiti can actually deter people from engaging in vandalism graffiti (2010:57). This confirms the idea that art graffiti has a place in a neighborhood like Kerrisdale, because it represents the community through deterring unwanted vandalism graffiti, and through its artistic representation of the community.

Like Lauren and Marias and Taylor, Erika believes that graffiti can be excellent for a community, reinforcing, the fact that the presence of public art graffiti reduces incidences of vandalism graffiti and stating that art graffiti promotes creativity and “a sense of community.” However, Erica’s main purpose is to examine the history of graffiti. In doing so she concludes that graffiti has evolved into something with all the characteristics of a legitimate art form, but its history of association with gangs and violence taints the image of art graffiti. She continually advocates the idea of graffiti artists as true artists, and says that, “Hateful graffiti is being removed to make way for the new era of graffiti… where… works of art can be admired and appreciated for what they are.” Erika indicates, however, that this process is not complete and for many people graffiti is still associated with crime; this is where Lauren’s blog compliments Erika’s. Lauren’s clear differentiation between the two types of graffiti makes way for art graffiti and vandalism graffiti to exist as separate entities, without the negative associations people currently have of the word crossing into the art side. Gomez reinforces this idea, stating that as the law fails to recognize some graffiti as art, it is inevitable that people will as well (1993:697). Thus with clearer distinction between graffiti art and graffiti vandalism, it will be possible to recognize graffiti art as art, which can have a positive contribution to communities.

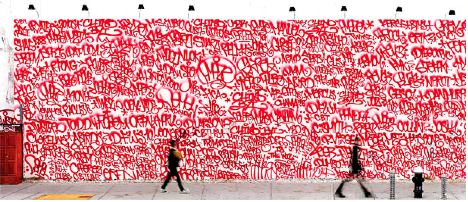

Finally, to return to the idea of art graffiti, Metcalf says that anything can be art, but only if recognized as such by the “artworld” (1997:68). Last month, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) showcased the first major U.S. exhibition of solely graffiti and street art, focusing portions of its exhibit on graffiti as it relates to the wider context of its community. The graffiti artists showcased at MOCA are finally getting recognition as legitimate artists by those in a position to confer that status on them. Additionally, those same people recognize that graffiti is closely tied to its community. This exemplifies Erika’s position that graffiti’s image has changed, and Erica and Lauren’s shared idea of art graffiti as a medium facilitating positive representations of a community.

|

| Graffiti image from MOCA. http://www.moca.org/audio/blog/?p=1522 |

Works Cited

Gomez, Marisa A.

1993 Writing on Our Walls: Finding Solutions through Distinguishing Graffiti Art from Graffiti Vandalism. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform. 26(Spring): 633-708.

Lauren

Graffiti: Cultural and Coail Construction Stemming form art or vandalism? http://anth378-lauren.blogspot.com/

Marais, Ida and Myra Taylor

2009 Does Urban Art Deter Graffiti Proliferation? An evaluation of an Austrailian commissioned urban art project. In British Criminology Conference. British Society of Criminoology. www.britsoccrim.org/conferences.htm

Metcalf, Bruce

1997 Craft as Art, Culture as Biology. In The Culture of Craft: Status and Future. Peter Dormer, ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Museum of Contemprary Art.

2011 Announcing Art in the Streets. http://www.moca.org/audio/blog/?p=1522

Szarbathy, Erika